Karst

| The term ‘Karst’ usually refers to either features or terrain formed by dissolution. Think holes. Water erodes soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum creating features like caves, sinkholes, and springs. Karst landscapes are characterized by underground drainage systems where surface water and groundwater systems are linked. A quarter of the world’s population depends upon water supplied from karst areas. |

Texas Karst

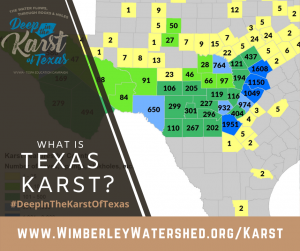

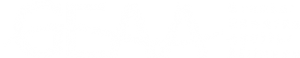

Texas has over 15,000 documented caves, sinkholes, and springs. Since the 1950s, cavers have been actively mapping karst features, and their data are managed through the Texas Speleological Survey (TSS). Texas has several karst zones with a substantial number of karst features.

Texas has over 15,000 documented caves, sinkholes, and springs. Since the 1950s, cavers have been actively mapping karst features, and their data are managed through the Texas Speleological Survey (TSS). Texas has several karst zones with a substantial number of karst features.

County karst feature totals including the number of caves, springs, sinkholes, and other karst features are compiled by the TSS.

Several of the rock layers that make up the Edwards, Trinity, and Edwards-Trinity Plateau aquifers are well-known for cave development, and a large number of documented karst features correlate to where those rock layers are exposed at the surface–such as in Bexar, Comal, Hays, Travis, Williamson, and Bell Counties.

Texas Karst Waters

Some of Texas’ karst aquifers are known for high groundwater flow rates, fresh water, and rapid recharge. Well, over two million people rely on groundwater stored in karst aquifers as their sole water supply. There are at least 12 federally-listed endangered species that only live in karst aquifers and springs. Karst springs range from large, well-known swimming holes to small seeps that provide baseflow to creeks and rivers. Spring flow is an indicator of groundwater conditions in the source aquifer and is often used to inform coordinated water conservation programs.

Benefits and Threats in Karst Landscapes

Caves and sinkholes provide direct access for surface water into the groundwater system. Karst aquifers are unique in that they can recharge quickly and replenish critical groundwater supplies. However, spills, point and non-point source pollution, development, and construction on the surface can quickly impact groundwater quality. Conservation easements, water quality protection lands, parks, and open spaces in critical recharge areas allow land to be managed to optimize and protect recharge.

We are the karst landscape’s beneficiaries —

and its greatest threat.

Karst Education Activities

TESPA and The Watershed Association Come Together Again To Educate, Advocate, and Protect.

We may know and treasure our iconic great springs and nearby karst caves, but this International Year of Karst and Caves is a time to get to know and better understand the whole rocky system with holes through which the water flows, that powers creeks and streams to form our great rivers and carve great rolling vistas from the ancient shallow seas that once covered the land.

Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, and subscribe to our Newsletters to stay in the loop! We invite you to donate to help boost local karst education and protection efforts. The Karst Walk and Neighborhood Site Visits – Trinity Aquifers are two programs made possible by funding from The Water Protectors Fund.

Karst 101

Karst and Water Quality

What is an Aquifer?

Imagine this rock full of water… hundreds of feet below where you are standing (or sitting). Simply defined, an aquifer is a rock layer or group of rock layers that hold groundwater. Sandstone, limestone (pictured), alluvium (river deposits), gravels, and even volcanic rocks can be aquifers. [Spoiler: most Hill Country well owners tap into karst limestone aquifers.]

Aquifers have different water quality characteristics related to their recharge rates, how long the water has been stored in the rock (residence time), and the chemical composition of the rocks themselves.

Groundwater can dissolve the rock around it—depending on how soluble the rocks are and the water’s residence time. The more dissolved minerals there are in the water, the ‘harder’ the water is. Most well-owners know hardness as spots on dishes and calcium deposits on plumbing fixtures—that is part of the aquifer moving its residence to yours!

What is a Karst Aquifer?

Imagine rocks with holes (big and small) full of water! Karst aquifers are exceptional in that their rocks and rock layers can have caves, conduits, and large void spaces (holes) to hold and move water underground. The location and size of caves and conduits are often unpredictable, though some rock layers and fault zones are more prone to karst feature development. The karst conduit system allows for rapid water flow from the surface into the aquifer and within the aquifer itself.

This SCUBA diver is in the Jacob’s Well cave passage in Cow Creek Limestone–which is part of the Middle Trinity Aquifer. The Cow Creek limestone is unique in that it is easily eroded and has many documented caves and springs, like Jacob’s Well, Pleasant Valley Springs, and Rebecca Springs. The Middle Trinity Aquifer includes the Lower Glen Rose Limestone, the Hensel Sand, and the Cow Creek Limestone. The Hammett Shale provides the impervious layer below separating the Middle Trinity Aquifer from the Lower Trinity Aquifer underneath.

The Edwards Aquifer and all three Trinity Aquifers (Upper, Middle, and Lower) are all karst aquifers. Millions of Central Texas residents depend on these aquifers for drinking water.

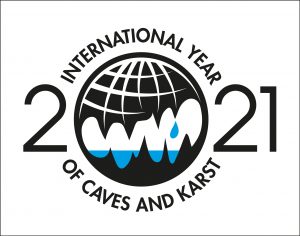

How Does a Karst Aquifer Recharge?

Karst aquifers recharge quickly. The caves and sinkholes at the surface provide direct access to the groundwater system below. This is beneficial in that groundwater storage and water levels recover during wet periods. But rapid recharge can also carry contaminants from the surface into the groundwater system. In karst landscapes like the Hill Country, what happens at the surface directly affects the water quality below.

Nitrate/nitrite and bacteria screening are good indicators of a well’s surface connection since they’re not naturally found in the aquifer systems. Nitrate and nitrite would come from fertilizers, livestock, wildlife, or septic systems. And bacteria—especially E. Coli bacteria, come from the gut (or digestive system) of a warm-blooded animal. The EPA and many groundwater districts suggest that well owners test their well systems annually to ensure water is safe to drink. Well-owner resources, links to treatment system options, and water quality testing options are available on the Home Owner Resource Page.

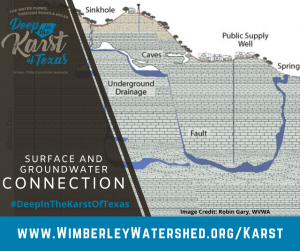

Surface and Groundwater Connection

What happens at the surface affects the groundwater below in karst landscapes. Karst features (caves, sinkholes, solution-enlarged faults & fractures) funnel water quickly into the underground drainage system. This groundwater is stored in karst aquifers, which supply many wells and provide source water for springs and rivers.

What happens at the surface affects the groundwater below in karst landscapes. Karst features (caves, sinkholes, solution-enlarged faults & fractures) funnel water quickly into the underground drainage system. This groundwater is stored in karst aquifers, which supply many wells and provide source water for springs and rivers.

While rains provide recharge to the groundwater supplies, they can also wash contaminants from the surface into the groundwater system below. Karst landscapes like ours are sensitive to development, which underscores the need for stewardship and innovation to protect habitat, water supplies, and the beauty of the Hill Country.

What is Karst?

To understand karst, think of holes. If you’ve been to the Hill Country, you’ve seen lots of holey rocks and they’re a key part of what makes the Hill Country unique.

The Hill Country is a karst landscape. ‘Karst’ usually refers to either features or terrain formed by dissolution. Water erodes soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum creating karst features like caves, sinkholes, and springs. Karst landscapes are characterized by underground drainage systems where surface water and groundwater systems are linked through karst features.

A quarter of the world’s population depends upon water supplied from karst areas. Well over 2 million people rely on the Edwards and Trinity Aquifers in central Texas and millions more visit and swim in karst springs like Comal, San Marcos, Barton, Hueco, and Jacob’s Well Springs.

What is Texas Karst?

Deep in the Karst of Texas…. But where you might ask!? Texas has several karst regions. These are areas where soluble rocks are at the surface and through time water has eroded those rocks creating karst features like caves, sinkholes, and springs. Since the 1950s, cavers have mapped over 15,000 karst features in Texas and their data are managed through the Texas Speleological Survey (TSS).

Many of the rock layers that make up the Edwards, Trinity, and Edwards-Trinity Plateau Aquifers are well-known for cave development, and a large number of documented karst features correlate to where those rock layers are exposed at the surface–such as in Bexar, Comal, Hays, Travis, Williamson, and Bell Counties.

Texas Karst Waters

You’ve already experienced Texas’ karst waters if you’ve 1) been swimming in one of the many Hill Country springs like Jacob’s Well (pictured), Barton Springs, Comal Springs, or Hueco Springs; 2) canoed, tubed, or splashed in the Guadalupe, San Marcos, Blanco, or Pedernales Rivers—to name a few; 3) sipped a cool glass of tap water in the Hill Country or I-35 corridor, including towns like Wimberley, Boerne, Kyle, Buda, San Marcos, New Braunfels, or San Antonio.

Karst springs range from large, well-known swimming holes to small seeps that provide baseflow to creeks and rivers. Spring flow is an indicator of groundwater conditions in the source aquifer and is often used to inform coordinated water conservation programs. Texas’ karst aquifers are drought-prone just like lakes and rivers. Well, over two million people rely on groundwater stored in karst aquifers as their sole water supply.

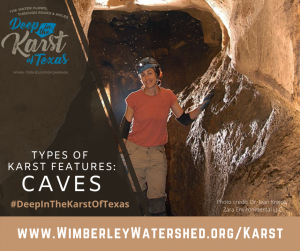

Karst Features: Caves

Texas is full of famous, infamous, and locally-known, wild caves. As recharge features and habitats, caves are an essential part of the Texas landscape. Technically, karst features big enough for a human to enter are considered caves. Caves can rapidly channel water from the surface into the groundwater systems (aka, aquifers) and provide shelter from extreme Texas temperatures.

Natural Bridge Caverns, Inner Space Cavern, Longhorn Cavern State Park – Texas Parks and Wildlife, Wonder World Cave & Adventure Park, and Caverns of Sonora are all Texas show caves and visitors can enter the cool underworld for a glimpse of recharge from below. It’s a great Texas summer activity! If you’d like to explore wild caves, find your local Grotto (caver organization) and ask about training trips. Be safe, make a plan, have the right equipment, and go with an expert.

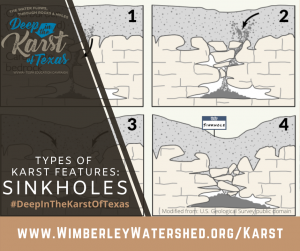

Karst Features: Sinkholes

Sinkholes are aptly named karst features. They act like natural sinks with a basin and a drain below. Rainfall pools at the surface, and the water infiltrates and erodes away the rock below creating pathways for the water to flow down underground. With each rain, water moves sediment from the surface down through the drainage system leaving a depression at the surface. The tricky part about sinkholes is that caves can form below the surface and with enough erosion, thin layers of rock can collapse and create a grotto-like Westcave Outdoor Discovery Center or Hamilton Pool, Travis County Parks

Sinkholes are aptly named karst features. They act like natural sinks with a basin and a drain below. Rainfall pools at the surface, and the water infiltrates and erodes away the rock below creating pathways for the water to flow down underground. With each rain, water moves sediment from the surface down through the drainage system leaving a depression at the surface. The tricky part about sinkholes is that caves can form below the surface and with enough erosion, thin layers of rock can collapse and create a grotto-like Westcave Outdoor Discovery Center or Hamilton Pool, Travis County Parks

Karst Features: Springs

Springs are magical. They’re beautiful. And in the Hill Country, there are lots of them!

Karst springs range from large, well-known swimming holes to small seeps that provide baseflow to creeks and rivers. Each spring tells an important groundwater story.

Sinkholes, faults, and fractures exposed at the surface can channel water underground, and through time, water creates flow paths that carry more and more water, which erodes away more and more rock enlarging the flow paths into conduits or caves. Karst conduit systems are highly developed underground flow paths that can carry water quickly from recharge (where water enters the groundwater system) to spring flow (where groundwater emerges at the surface).

Luckily, not all the water that enters the groundwater system comes out of springs. Some water gets trapped within the holes and pores in the limestone itself—moving slowly and adding to the groundwater stored in the aquifer. After a rain, flow from karst springs increases quickly as the stormwater moves through the conduits, then it subsides–often slightly higher than it was before the rain, if enough recharge entered the system to boost storage in the aquifer. Spring flow is an indicator of groundwater conditions in the source aquifer and is often used to inform coordinated water conservation programs.

Friends of Karst

The Wimberley Valley Watershed Association partners with many organizations to help protect, educate, and advocate for the sensitive karst landscape and karst water resources of the Hill Country. Find out more about the Friends of Karst by clicking on their logos.