Hill Country Urbanism—A case study of Jacob Well

In the fall of 2017, the Jacob’s Well Studio seeks to continue the mission of the Hill Country Studio in imagining a sustainable future for the Hill Country, one that preserves the region’s natural resources, especially water, as well as the rich blend of cultures that make the region distinctively Texan. In partnership with the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association (WVWA), the Jacob’s Well Studio produced three proposals for a site near the Village of Wimberley and the Jacob’s Well spring. WVWA was the imagined client of a development team. Each proposal is intended to show a feasible alternative pattern of development while considering today’s context.

The studio’s objectives are:

-

- To understand the roles and potential of each discipline in the urban built environment

through physical planning and urban design - To be able to develop critical strategies that address economic, social and environmental

implications in the urban context through the process of analysis, case study evaluation and collaborative practice - To be able to graphically and verbally communicate design strategies and complex urban

issues to a wide audience including professionals and the general public - To become comfortable using GIS, Indesign, Photoshop, Sketchup and other graphic related software to present physical planning and urban design content.

- To understand the roles and potential of each discipline in the urban built environment

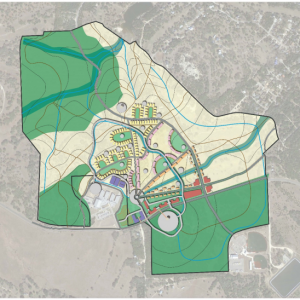

The proposals seek to test the concepts presented by the proposed Hill Country Regional Plan, creating a high-density, water-neutral development which accommodates population growth while maintaining open space. The project site, part of Woodcreek North, is currently owned by a private developer and platted for quarter-acre parcels and single-family, detached homes. However only a minority of the parcels are sold, and fewer still have homes on them. The project site boundaries are drawn around multiple undeveloped parcels, encompassing both sides of Ranch Road 2325 roughly a mile and a half from downtown Wimberley. The Jacob’s Well Elementary School and Wimberley ISD Baseball and Softball complex both border the project site, as does an AquaTex water treatment plant.

The scope of the class is to create a new master plan for the designated site as per the client’s goals and programmatic elements listed below to ideally include water neutral, low impact development.

The plan will include the following desired features:

-

- 250- 500 units of housing – single-family, multi-family, townhome

- Energy and water efficient commercial/retail space including live/work spaces

- Walkable mixed-use town center, village, or hamlet with green streets

- Community Space including meeting space and non-profit office space

- Affordable housing and community land trust

- Climate appropriate agricultural production (micro-farm, permaculture) and gardens

- Open space network with parkland, trails and diverse natural habitats that promote clean and abundant aquifer recharge

Finally, the students were directed to: “develop a “Hill Country Urbanism” as an alternative to typical suburban development in the Hill Country”. This means considering “the conclusions of the Hill Country Studio to propose a high-density, low-impact model of development in the region,” and considering “the water, ecology, climate, culture, and genus loci of the Hill Country in design.”

The goals for the student proposals are ambitious, and few precedents exist to guide students in their design. New Urbanist developments are more frequently found in existing cities, such as the Mueller development on the site of the former city airport in Austin, TX. Greenfield New Urbanist developments can create vacation enclaves, such as Seaside, FL.

Perhaps the closest contemporary precedent is Serenbe, GA, a sort of 21st century garden suburb at the edge of Atlanta. Serenbe created three “hamlets”, Selborne, Mado, and Grange, where homes and businesses cluster. The names are evocative of the community’s identity: “Mado” is a Creek Indian word for “in balance”, “Grange” is agriculture-themed, and “Selborne” is named for an English arts village. In between the hamlets are large pockets of green space, kept relatively intact by exurban standards.

Walkability is a high priority, and streets are narrow to calm traffic. In terms of sustainability, Serenbe comes up short compared to the Jacob’s Well Studio requirements. Serenbe pursues sustainability “by facilitating geothermal, solar, and net zero homes” and conserving water by “naturally treating our wastewater for ornamental irrigation”.

The Jacob’s Well Studio is much more ambitious by sustainability metrics. Indeed, Serenbe recalls a development typology that has been dormant in America for almost a century: the garden city. The American expression of an English ideal were suburbs such as Radburn, N.J. and the New Deal “greenbelt” towns of Greenbelt, MD, Greendale, WI, and Green Hills, OH. These towns designed for the pedestrian experience, preserved continuous green space with moderate housing density, and created an arcadian living experience in the suburbs. Like Serenbe, great emphasis was placed on their “natural” setting.

The Jacob’s Well Studio is not unlike these case studies in its vision of creating a sort of garden city, but one for the 21st century. It differs from developments that have come before it in its strong environmental ethic. Water neutrality is an engineering challenge for an area that suffers from frequent floods and droughts, but the technology is there. This is true of energy neutrality as well. Today, practices of land management are well-documented, from Brad Lancaster’s work on water harvesting to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s work on prescribed burns in the Hill Country. The land that the development sits on can take on a role of its own in a sort of “regenerative” development that seeks to exceed simple sustainability.