On September 11, community members, city officials, and staff from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) gathered in Blanco to debate the future of the city’s wastewater treatment plant permit. The packed hearing combined an informal Q&A session with a formal comment period, giving residents, scientists, and conservation groups the chance to weigh in on the health of the Blanco River.

[Photo: Blanco River below Blanco Waste Water Treatment Plant when Discharging Effluent]

[Photo: Blanco River below Blanco Waste Water Treatment Plant when Discharging Effluent]

City’s One Water Commitment

Mayor Candy Cargill highlighted the city’s adoption of a One Water resolution and reaffirmed Blanco’s aspiration to eliminate discharges. “For the past 18 months, not a drop of treated wastewater has been released into the river,” she said. “Every gallon has been reused through irrigation and land application. Our aspiration is zero discharge into the Blanco River.”

City Administrator Warren Escobedo and City Engineer Rachel Lumbreras emphasized that discharges only occur as a last resort when storage and irrigation fields are full. They noted the city has not discharged since February 2024 and has expanded irrigation acreage, while beginning discussions on purple-pipe reuse projects for schools and parks. Still, they acknowledged financial limits—residents pressed hard on why the city might spend $500,000 on a discharge pipeline rather than investing in storage and reuse. The question remains: Can the city locate and build out additional TLAP acreage before a discharge is required? And, without a strong permit, will these commitments outlast the next election cycle?

Conservation Advocates: Permit Too Weak

Conservation advocates praised Blanco’s recent no-discharge record but insisted the draft permit is too weak and does not reflect that commitment. Rather, it permits high nutrient discharge, in significant amounts, at any time, without public notice, and gives the City a three-year grace period with even lower standards for filtration. Lauren Ice, attorney for the Watershed Association, flagged that the draft actually allows a higher CBOD (Carbonaceous Biochemical Oxygen Demand) limit than the 2015 permit, violating the Clean Water Act’s anti-backsliding rule. She also criticized the three-year compliance period for phosphorus, calling it “unreasonable and unlawful.”

CBOD (Carbonaceous Biochemical Oxygen Demand): the oxygen microbes use to break down carbon-based organics in wastewater; higher CBOD means greater oxygen depletion in receiving waters.

Scientific data show background phosphorus in the Blanco averages just 0.01 mg/L, while the draft permit would allow up to 0.15 mg/L after three years, fifteen times higher. “Even small increases fuel algae blooms,” Ice warned, citing studies showing blooms triggered at levels as low as 0.02 mg/L. The Blanco River contains recharge features for the Trinity Aquifer, which supplies groundwater to hundreds of downstream neighbors. This permit allows for real threats to the local groundwater supply, as well as safe recreation in the river. [Read More: View the Full Meeting Presentation]

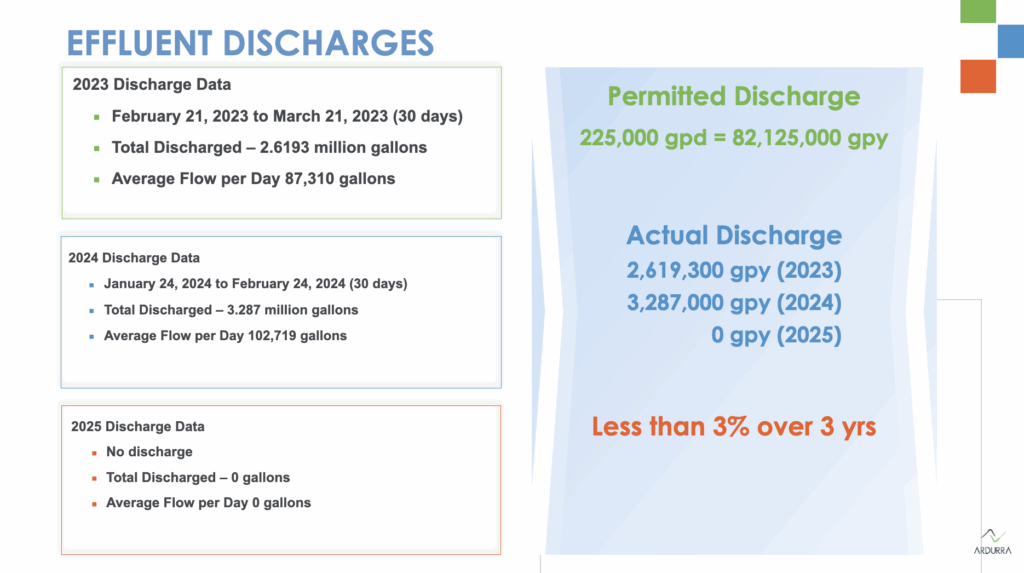

Photo above: City of Blanco Effluent Discharges into Blanco River 2023-2025

Photo above: City of Blanco Effluent Discharges into Blanco River 2023-2025

David Baker, Executive Director of the Watershed Association, underscored the stakes: “This river is the lifeblood of the Hill Country. The draft permit risks its health. We need more storage, more land, and more reuse—not infrastructure that normalizes discharge. In the last permit cycle, we proved collaboration works—partners from the city, Meadows Center, and local advocates came together to identify funding and reuse strategies. We can do it again. The pathway to zero discharge is real if we commit to it.”

The Save Barton Creek Association (SBCA) echoed these concerns in written comments, adding that the Blanco qualifies as a Pristine Stream under proposed legislation. Allowing phosphorus at the levels in the draft permit, SBCA argued, “would be a recipe for ecological damage.”

Citizens Speak — and Sing

Residents called for greater transparency, asking the city to give public notice before any discharge events. Others urged using treated water for irrigating soccer fields, hay fields, and school grounds, rather than building a pipeline to the river. Citizens made the call to local landowners and officials to think creatively about good uses for this valuable, high-nutrient water.

One of the night’s most memorable moments came when musician Bill Oliver gave his comment in the form of a song. With a pointed chorus of “It’s up to you, TCEQ,” the performance drew smiles, applause, and reflection, underscoring the community’s expectation that the agency must stand up for the river.

Collaborative Path Forward

To update the Wastewater system in a small town like Blanco requires collaborative, innovative thinking. Jason Pinchback closed with a call for partnership: “We want to be partners with you all to achieve that. We’re committed to working with the city and with TCEQ to find the funding and the land needed to expand storage and irrigation, so we can get to zero discharge.”

Next Steps

TCEQ staff confirmed that all oral and written comments from the hearing will be reviewed and addressed in a formal response to the comments document. That response, along with any permit revisions, could take up to six months. Any changes will be made public before the Executive Director issues a final decision. From there, parties may file motions for reconsideration or requests for a contested case hearing, potentially sending the permit to the State Office of Administrative Hearings.

In the meantime, the Watershed Association, the Blanco Conservation Initiative, and local residents and public interest organizations pledged to stay engaged and work with the City and Meadows Center for Water and the Environment to look for alternatives to the current permit and opportunities for additional funding for much-needed infrastructure improvements. The goal expressed by the City and the Community is to draft a permit that reflects science, honors Blanco’s One Water resolution, and secures a zero-discharge future for the river and aquifers that sustain the Hill Country.